When a parachute opens, many people think the parachutist suddenly shoots upward. This is not what really happens. The parachutist is always moving downward, but the parachute causes a very sharp deceleration. The large canopy produces a big upward drag force that slows the fall dramatically.

When people see videos of parachutists opening their parachutes, the camera angle can create a powerful illusion that the parachutist suddenly shoots upward. What really happens is that the parachutist decelerates sharply while the camera, usually attached to another skydiver, continues falling at almost the same high speed.

From the perspective of the camera, the parachutist with the open parachute is no longer keeping pace in the fall. The camera-holder is still dropping rapidly, but the parachutist has slowed down. In the video, this relative motion makes it look like the parachutist has bounced upward, when in fact they are still moving downward—just not as quickly.

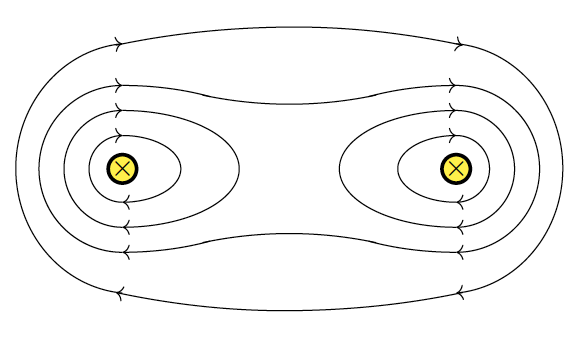

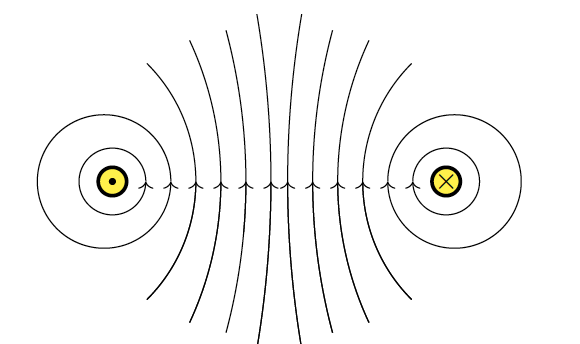

The physics of air resistance shows clearly why the velocity cannot turn upward. Air resistance always acts opposite to the velocity and its size depends on speed. Before and after the parachute opens, the parachutist’s velocity is downward, so the drag force must be upward. If the parachutist’s velocity really were upward, then the drag would have to point downward. In that case, the resultant force would also point downward, making the acceleration greater than gravity—something we never observe. Instead, the drag force remains upward, which proves the parachutist is still moving downward the whole time. The chute simply reduces that downward speed to a safe value.

For a simulation on how the forces and velocity change with time, refer to this GeoGebra app.