This app is an interactive tool for teaching how capacitors behave when connected in series and parallel. Students can enter values for two or three capacitors and switch between series and parallel arrangements to see how the total capacitance changes. By manipulating the capacitor values and observing the resulting total capacitance and underlying equations, learners build a deeper understanding of the rules for combining capacitors in circuits — such as how in series the total capacitance decreases and in parallel it increases.

Created a javascript simulation based on my previous GeoGebra app.

The Motion Kinematics Simulator is an interactive educational tool designed to bridge the gap between abstract physics concepts and visual intuition. By combining a real-time particle animation with a dynamic displacement-time graph, the app allows users to observe how various types of motion—such as constant velocity, acceleration, and deceleration—translate into specific mathematical gradients. You can scrub through the simulation to analyze velocity calculations or testing your knowledge in the integrated Quiz Mode.

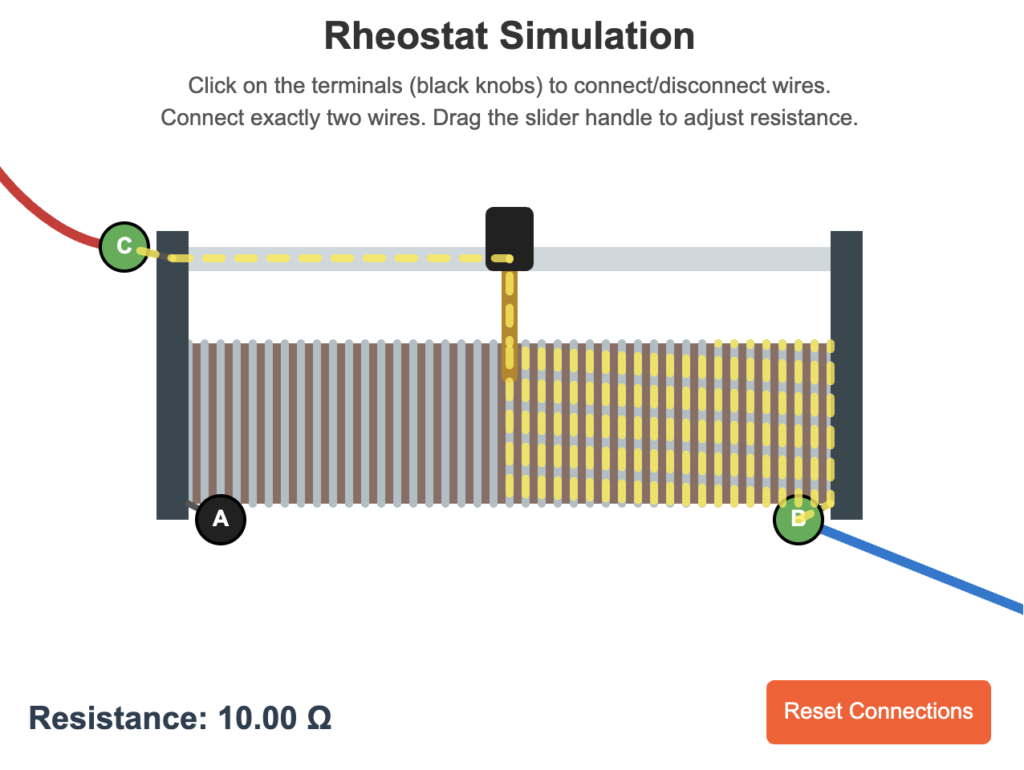

Open in new tab 🔗A rheostat controls the size of the electric current by changing the resistance in a circuit using a resistive track and a movable slider. Moving the slider changes the length of the resistive path, so a longer path gives a larger resistance and smaller current, while a shorter path gives a smaller resistance and larger current.

This morning, I was watching my students conduct an experiment with a rheostat and saw a few of them connecting the two lower plugs (A and B as shown in the simulation). I had to explain to them why the current would not change no matter how they move the slider. Then it occurred to me that this could be best explained using a simulation. So I created this simple simulation using a little vibe-coding to help my students visualise current flow through a rheostat, hopefully preventing them from connecting it the wrong way.

I used the following prompt on Trae.ai: “Create this html simulation of a rheostat. The canvas should show a realistic image of a rheostat with its three plugs. One above, next to the rod on which the slider is resting. Two on either side of the coil of wire. The user can connect two wires to any of the three plugs. The simulation should show the direction of current flow, from one terminal out to the other terminal. The resistance value will then be shown. Make the maximum resistance 20 ohm.”

It produced a working prototype within one prompt. I then made further prompts changes to refine the app. Trae.ai makes fast iterations much less painful as it only makes the changes to the necessary codes without having to generate the whole set of codes from scratch.

For Singapore teachers, this simulation is optimised for SLS and is directly embeddable to SLS as my github domain is whitelisted. Just paste the URL (https://physicstjc.github.io/sls/rheostat/) after clicking “Embed website”.

The Gorilla Physics Lab (created using Gemini Canvas) serves as a dynamic bridge between abstract projectile motion equations and physical intuition, transforming a classic gaming mechanic into a high-fidelity educational tool. By providing real-time relative physics data, such as horizontal displacement ($\Delta x$) and vertical height difference ($\Delta y$), the app encourages students to move beyond “trial and error.” Students are challenged to calculate the precise initial velocity or angle required to hit a target.

Furthermore, the simulation excels at visualizing the fundamental principle of the independence of $x$ and $y$ motion. Through the use of real-time vector arrows, students can observe how the horizontal velocity remains constant while the vertical velocity reacts to gravitational acceleration—shrinking as it approaches the apogee and growing as it falls. By toggling between different planetary gravities, from the light pull of the Moon to the crushing force of Jupiter, students gain a visceral understanding of how acceleration constants influence time of flight and parabolic curvature. Ultimately, the lab turns the classroom into an interactive environment where mathematical predictions are immediately validated by the motion of the projectile, fostering a deeper conceptual grasp of two-dimensional kinematics.

Bridging the Gap: A Digital Approach to Vector Scale Drawings

Vector addition is a fundamental concept in physics, yet students often struggle to visualize the connection between abstract numbers (magnitude, direction) and their geometric representation. I developed this Vector Scale Drawing App, a lightweight web-based tool designed to scaffold the learning process for vector addition, providing students with a “sandbox” to practice scale drawings with immediate feedback.

This Vector Scale Drawing App is not meant to replace pen and paper, but to complement it. A built-in guide walks novices through the process (Read -> Choose Scale -> Draw -> Measure).

“Pencil Mode”

The pencil mode allows students to make markings, trace angles, or draw reference lines without “committing” to a vector. Crucially, in Pencil Mode, the tools are “transparent” to clicks—you can draw right over the ruler, just like in real life.

This distinction helps students separate the *construction phase* from the *result phase*.

When students submit their answer (Magnitude and Direction), the app checks it against the calculated resultant. We allow for a small margin of error (5%), acknowledging that scale drawing is an estimation skill.

Base units are the fundamental building blocks from which all other units of measurement are constructed. In the International System of Units (SI), quantities such as length (metre), mass (kilogram), time (second), electric current (ampere), temperature (kelvin), amount of substance (mole), and luminous intensity (candela) are defined as base units because they cannot be broken down into simpler units. By combining these base units through multiplication, division, and powers, we can form derived units to describe more complex quantities—for example, speed (metres per second), force (newtons), and energy (joules).

This app teaches dimensional analysis by letting learners build derived physical quantities from the seven SI base units. Through an interactive fraction-style canvas, users place base-unit “bricks” into the numerator or denominator to form target dimensions (e.g., kg m⁻³ for density), reinforcing how exponents and unit positions encode physical meaning. Each quantity is accompanied by concise, inline hints that show the unit structure of the terms in its defining equation (for example, mass and volume in density, or force and area in pressure), helping students connect formulas to their base-unit foundations. By checking correctness and exploring more quantities (force, energy, power, electric charge, voltage, resistance, heat capacity, specific heat, latent heat, molar mass), learners develop an intuitive, transferable understanding of how physics equations translate into consistent SI units.

The app (https://physicstjc.github.io/sls/base-units/) can be directly embedded into SLS as the domain is now whitelisted.