This simulation lets you watch two equal-size spheres (light and heavy) fall, while you see their free-body diagrams (FBDs) and a velocity–time graph update in real time.

Press Start to run and Pause to discuss a moment in time. Reset restarts from rest. Use Zoom to read the force vectors clearly. Toggle Air Resistance to compare an idealised fall (no drag) with a more realistic one (drag on). The small info panel shows the current speeds and, when drag is on, each sphere’s terminal velocity.

What to look for

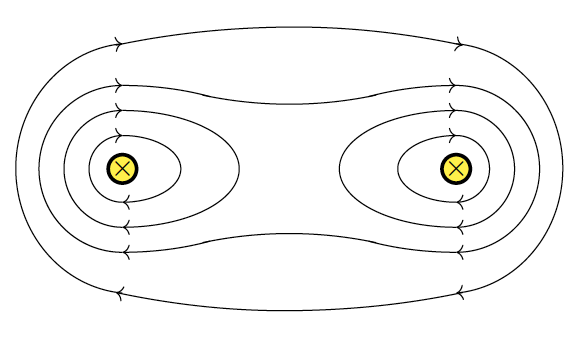

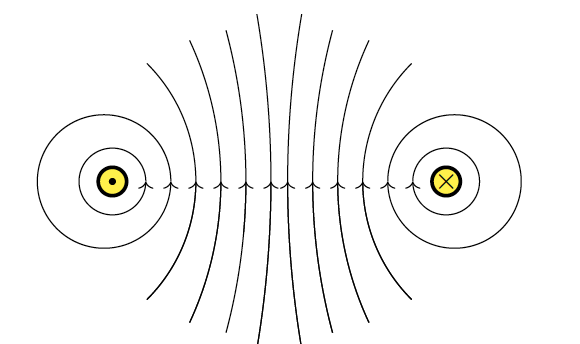

- Without air resistance: Each FBD shows only weight downward. Acceleration is constant at ggg, so the velocity–time graph is a straight line from the origin for both spheres (same slope, because mass doesn’t matter when no drag acts).

- With air resistance: A drag arrow appears upward and grows with speed. The heavy sphere’s velocity rises faster at first (its weight is larger), but both curves flatten as drag increases, and the acceleration vector shrinks toward zero. Dotted segments indicate when the two curves overlap closely.

Theory in one breath

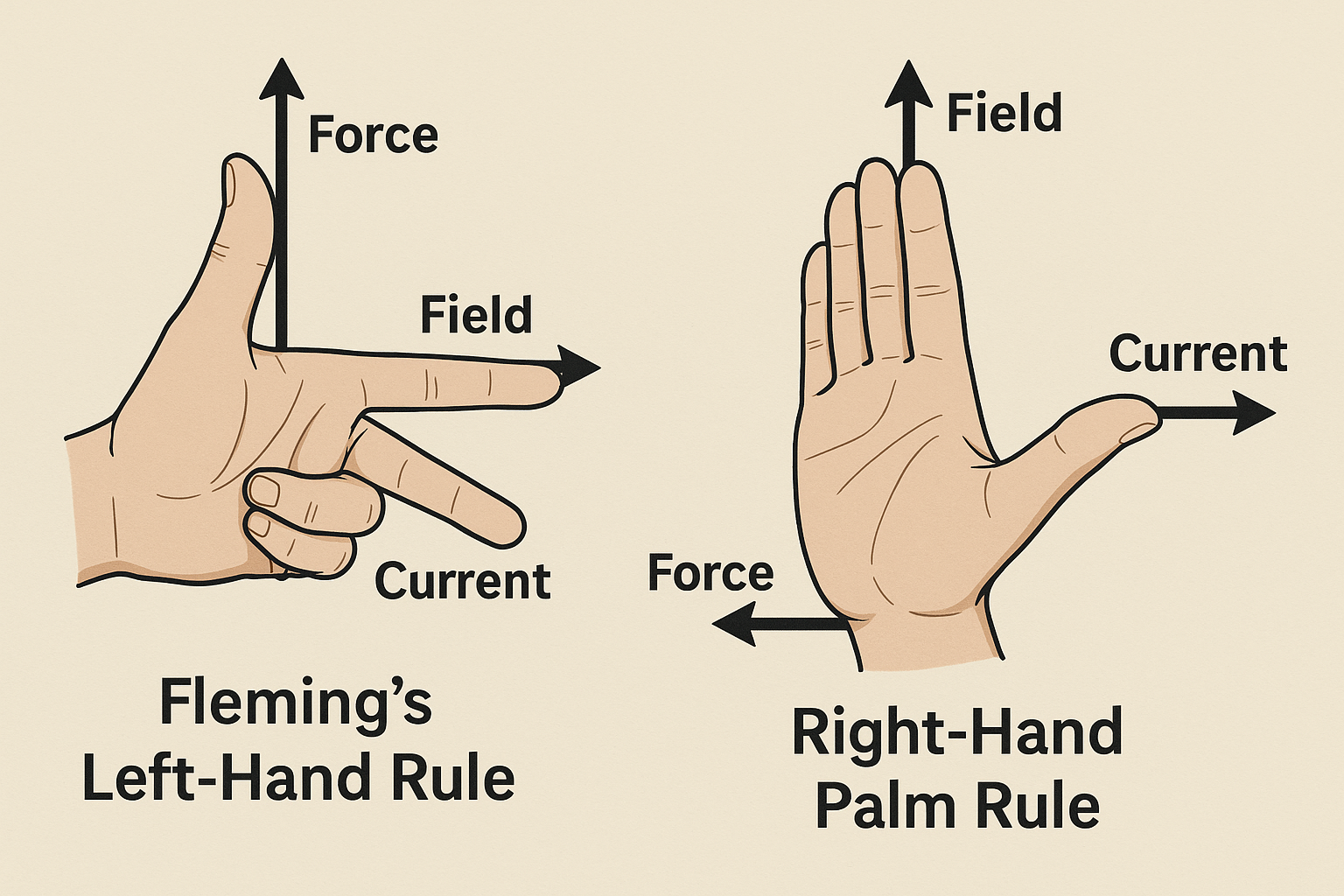

In air, we model drag as proportional to speed: $F_\text{drag}=kv$

Net force is $ma=mg−kv \quad\Rightarrow a=g−\dfrac{k}{m}v$

As v grows, the term $\dfrac{k}{m}v$ eats into $g$, so acceleration falls.

Terminal velocity happens when forces balance: $mg=kv$, so $v_t=\dfrac{mg}{k}$

Heavier mass ⇒ larger $v_t$. That’s why the heavy sphere ultimately settles at a higher speed and takes longer to level off. With drag off, the model is simply $a=g$ and $v=gt$.

How to teach with it (fast)

- Start with Air Resistance off: Pause after a second—ask why both lines match and why only weight appears on the FBDs.

- Turn Air Resistance on: Run, then pause midway. What changed in the FBDs? Why is acceleration smaller now?

- Let it run until the acceleration vectors nearly vanish: connect “flat graph” with “balanced forces,” then read off different terminal velocities.

That’s it: start, pause, notice which vector changed, and link the picture to the equation.