This interactive simulation helps students compare what happens in series and parallel circuits using two bulbs and a 6 V battery. Learners can switch between series and parallel configurations, adjust the resistance of each bulb, and see how this affects the current, voltage and brightness of the bulbs. By dragging the ammeter (A) into the circuit, they can measure the current through a chosen bulb, and by placing the voltmeter (V) across a bulb, they can measure the potential difference across it. The changing brightness of each bulb represents the power it dissipates, allowing students to visualise ideas such as: in a series circuit the current is the same through all components but the voltage is shared, while in a parallel circuit the voltage across each branch is the same but the currents can be different.

Metal Lattice Simulation

This simulation demonstrates the principle that the resistance of a metal conductor increases with temperature. As temperature rises, the metal ions in the lattice vibrate more vigorously. This increased vibration causes charge carriers (electrons) to collide more frequently with the ions, hindering their movement. As a result, resistance increases and the current flowing through the conductor decreases for the same applied voltage.

At the A-Level, this simulation extends the understanding of current by examining it from a microscopic perspective in terms of mean drift velocity. Instead of viewing current simply as the rate of flow of charge, students learn that electrons in a conductor move slowly on average, with a small net drift in the direction of the electric field. The current depends on how many charge carriers are available and how fast they drift. This is expressed using the equation:

$$I = nAv_dq$$

where is the current, is the number density of charge carriers, is the cross-sectional area of the conductor, is the mean drift velocity of the electrons, and is the charge of each carrier. As temperature increases, more frequent collisions reduce the drift velocity, helping to explain why current decreases even though the charge carriers are still present—linking microscopic behaviour with macroscopic electrical measurements.

When a parachute opens, many people think the parachutist suddenly shoots upward. This is not what really happens. The parachutist is always moving downward, but the parachute causes a very sharp deceleration. The large canopy produces a big upward drag force that slows the fall dramatically.

When people see videos of parachutists opening their parachutes, the camera angle can create a powerful illusion that the parachutist suddenly shoots upward. What really happens is that the parachutist decelerates sharply while the camera, usually attached to another skydiver, continues falling at almost the same high speed.

From the perspective of the camera, the parachutist with the open parachute is no longer keeping pace in the fall. The camera-holder is still dropping rapidly, but the parachutist has slowed down. In the video, this relative motion makes it look like the parachutist has bounced upward, when in fact they are still moving downward—just not as quickly.

The physics of air resistance shows clearly why the velocity cannot turn upward. Air resistance always acts opposite to the velocity and its size depends on speed. Before and after the parachute opens, the parachutist’s velocity is downward, so the drag force must be upward. If the parachutist’s velocity really were upward, then the drag would have to point downward. In that case, the resultant force would also point downward, making the acceleration greater than gravity—something we never observe. Instead, the drag force remains upward, which proves the parachutist is still moving downward the whole time. The chute simply reduces that downward speed to a safe value.

For a simulation on how the forces and velocity change with time, refer to this GeoGebra app.

This is a problem posed by a student today:

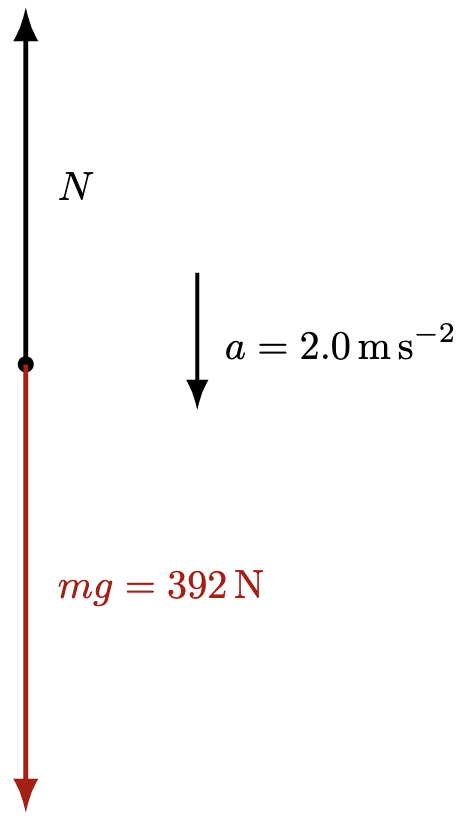

A boy of mass 40 kg is standing on a weighing machine inside a lift which is moving upwards. At a certain moment, the speed of the lift is $3.0 \text{ m s}^{-1}$ and it is decelerating at $2.0 \text{ m s}^{-2}$. What is the reading (in kg) shown on the weighing scale?

My advice for any dynamics problem is to take the direction of acceleration as positive. This way, you can apply Newton’s second law directly without worrying about inserting extra negative signs for deceleration. After all, a negative value of acceleration simply comes from the chosen sign convention—it reflects direction. For simplicity, putting the direction of acceleration as positive (in this case, downward is positive), we have

$$F_{net} = ma$$

The net force should therefore, be $W – N$, where $N$ is smaller than $W$.

$$W – N = ma$$

Substituting, we have

$$mg – N = ma$$

$$(40 \text{ kg} \times 9.81 \text{ N kg}^{-1}) – N = 40 \text{ kg} \times 2.0 \text{ m s}^{-2}$$

$$N = 312 \text{ N}$$

Note that $N$ is also known as apparent weight.

The mass reading due to this normal force = $\dfrac{312\text{ N}}{9.81 \text{ N kg}^{-1}} = 32 \text{ kg}$

(Notice here that the speed of the lift is irrelevant.)

The GeoGebra simulation allows you to modify the acceleration and observe the change in the vector representing the normal contact force, which is force acting on the weighing scale.

Open in new tab 🔗For a real-life experiment along with a visualisation of the changes in the vectors based on this scenario, check out my video and simulation.

When tackling kinematics problems, a quick way to decide which equation to use is to look carefully at which variables are given and which one you need to find. The four equations involve only five quantities — $u$ (initial velocity), $v$ (final velocity), $a$ (acceleration), $t$ (time), and $s$(displacement). Each equation links four of them, leaving one out. So if, for example, time $t$ is not mentioned anywhere in the problem, the best choice is usually the equation $v^2 = u^2 + 2as$, since that one does not involve $t$. By matching the known and unknown quantities against the “missing variable” in each equation, you can quickly narrow down the correct equation to apply.

Interact with the simulation of an electrostatic precipitator (ESP) above. The ESP is a big air cleaner for factories and power plants. It uses electricity to pull tiny dust and mist out of smoky gas before the gas goes up the stack. Inside the box are thin wires kept at a very high voltage next to large metal plates that are grounded. The high voltage makes a faint “corona” around the wires, which is a cloud of charged ions. As the dirty gas flows past, those ions bump into the dust particles and give them an electric charge, kind of like when a balloon rubs on your sweater and becomes “static.”

Once the particles are charged, the electric field pushes them sideways toward the plates. Positive particles are pulled one way, negative the other, but either way they end up sticking to a plate instead of staying in the air stream. The cleaned gas keeps moving forward and exits the ESP. Every so often, the plates are cleaned: in a dry ESP, mechanical “rappers” gently shake the plates so the dust falls into hoppers; in a wet ESP, water rinses the plates so sticky mist and very fine droplets wash off.

ESP performance depends on keeping the electric field strong and the gas flow smooth, and on the dust being “just right” electrically—if it holds charge too well or not well enough, efficiency drops. When everything is tuned properly, an ESP can remove well over 99% of particles with very little resistance to airflow. That’s why they’re widely used to protect the air around power plants, cement kilns, and other heavy industries.